Regret.

If we think the price of success is too high, wait until we get the bill for regret.

“Fear is temporary. Regret is permanent.”

Regret is a negative cognitive or emotional state that involves blaming ourselves for a bad outcome, feeling a sense of loss or sorrow at what might have been, or wishing we could undo a previous choice. (1)

“Regret is a common part of our lives, and it’s something that we see … in people of all walks of life,” said study researcher Neal Roese, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University.

What Do We Regret?

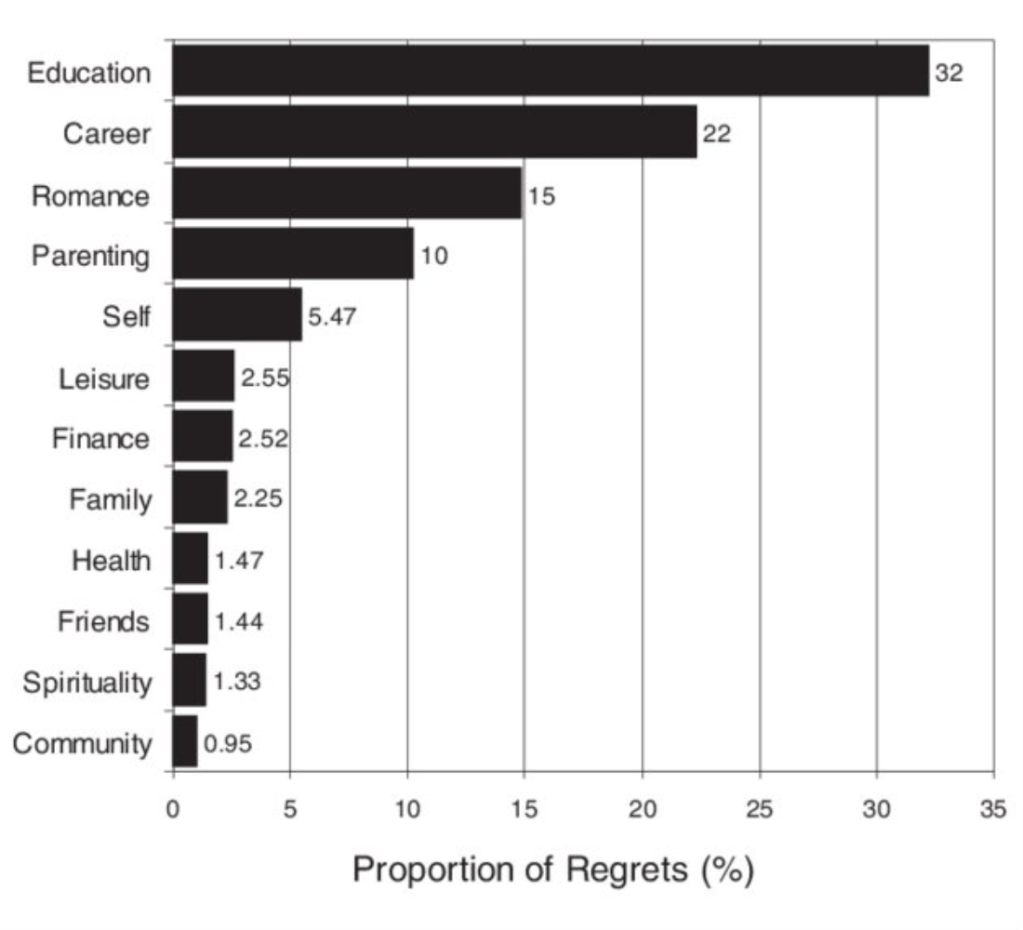

The chart above represents a meta-analysis of 11 regret ranking studies that revealed that the top six biggest regrets in life center on (in descending order) education, career, romance, parenting, the self, and leisure. Education is our most significant regret by a long shot. One-third of the study population wants a do-over of their school days. Understandably, poor career choices litter our conscious history.

Contemporary Americans have enormous freedom in dating, marriage, and divorce, yet it is not always this way. Might regret centering on romance be more common today than a century ago, when people married young, divorced rarely, and saw few opportunities for alternative romantic partners? (2)

Regrets are balanced between the genders, except for relationships. Studies on gender differences show women value relationships more than men. Consequently, women have more difficulty disengaging attention from past relationships. In one study, 44 percent of women surveyed had romantic regrets versus just 19 percent of men. “There’s a general idea in research that women are more concerned with social relationships than men are. Men are more concerned with career and self-advancement,” said Joachim Krueger, a professor of psychology at Brown University who has researched gender stereotypes.

Dr. Seema Hingorrany, a relationship expert, says, “Women naturally navigate more emotionally than men, and that is why they analyze and suffer more when a relationship does not work out.”

Action versus Inaction

Researchers have found two forms of regret:

- regret for what one did not do, missing out/not taking advantage of opportunities when they arose (inaction)

- regret for what one did, including mistakes, poor choices, missteps, etc. (action)(3)

Wired to Regret

Many experts view regret as a mental phenomenon conditioned by evolution. We have an evolutionary advantage as a species to learn from previous mistakes. And to remember those mistakes to avoid similar mistakes in the future. Our past experience lingers as a cautionary tale paving the way for better choices. Our future actions have more forethought, awareness, and wisdom through the lens of regret. Though often seen as distressing, regret pushes all the positive evolutionary buttons ensuring our survival.

What can we do with our Regret Wiring?

As mentioned above, many experts view regret as a mental phenomenon conditioned by evolution. What can we do with our regret wiring?

a) Decision Preparation. Consider the circumstances that may have made it more challenging to make good choices in that particular instance or that you had limited knowledge of at the time. Perhaps you had to make a quick decision under time pressure or had multiple stresses. Regret’s lesson is to step back. Conduct more research before making similar decisions.

b) Deeper meanings. Think about life as a journey. Everybody makes mistakes. They can be opportunities to learn important lessons about yourself—including your values, vulnerabilities, and triggers—and about trusting or depending on others. You can also use past regrets to decide how to take better care of yourself in the future. And how to better access others we bring into our lives and the boundaries we draw.

Researcher Neal Roese, a leader in the field of regret research, says his studies of younger people have shown that regret was rated more favorably than unfavorably, primarily because of its informational value in motivating corrective action.

The Downside of Regret

Kathryn Schulz, author of Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error and presenter of the compelling TED Talk “Don’t Regret Regret,” summarizes scientific research indicating that the onset and persistence of regret typically move through a sequence of phases, which include:

(1) denial (just make the wrong thing I did go away);

(2) bewilderment (a sense of alienation in which a person cannot believe they participated or caused some situation or outcome to occur, i.e., a sense of being out of one’s mind);

(3) the desire to punish oneself for a mistake or poor choice; and

(4) ruminations (persevering on what occurred, i.e., thinking about it repeatedly with self-contempt).

Regret becomes problematic when chronic cycling between phases 3 and 4 occurs. The less opportunity one has to change a negative situation he or she caused, the more likely ruminative cycling will occur, potentially leading to intense sorrow, self-degradation, anxiety, and depression.

The Physical Effects of Regret

Regret can damage the mind and body when it becomes fruitless rumination and self-blame that keeps people from re-engaging with life. This pattern of repetitive, negative, self-focused ruminative thinking is characteristic of depression and may also cause this mental health problem.

Regret can result in chronic stress, negatively affecting hormonal and immune system functioning. Regret impedes the ability to recover from stressful life events by extending their emotional reach for months, years, or lifetimes.

The real benefit of regret is not correcting our mistakes but realizing we can evolve into better decision-makers.

Until next time. Travel safe.

Footnotes.

(1) Greenberg, Melanie The Psychology of Regret Psychology Today Online May 16, 2012, http://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-mindful-self-express/201205/the-psychology-regret

(2) Roese, Neal & Summerville, Amy. (2005). What We Regret Most … and Why. Personality & social psychology bulletin. 31. 1273-85. 10.1177/0146167205274693.

(3) Tobin, James The Psychology of Regret The James Tobin Ph.D. website August 21, 2020, https://jamestobinphd.com/the-psychology-of-regret/