Distractions.

“We must fall in love with our passions, not our distractions.”

We can't do big things if we are distracted by small things.

On my morning run, my right knee began to ache. At the end of my run, my iPods in their case went into my sweatpants. Focused on the ache and not my routine, I automatically peeled my wet clothes off, chunking them into the washer. Distracted by discomfort, I was sleepwalking through the morning. I would never knowingly throw technology into a washer. My iPod debacle illustrates how quickly and easily we can be nudged out of our routines resulting in degrees of chaos.

How many of us have done something without really thinking? Remember brushing our teeth or driving to work this morning? For many of us, everyday rituals are things we can do almost automatically. Often referred to as acting or being "zoned out" or on "autopilot." The ability to do tasks, rituals, and routines without thinking is an example of a phenomenon psychologists call automaticity. No matter the label, we are only partially present.

Automaticity is the ability to do things without occupying the mind with the low-level details required. It is usually the result of learning, repetition, and practice.1

Automatic thoughts and behaviors occur efficiently without needing conscious guidance or monitoring. Most thoughts and behaviors tend to be automated or have mechanical components. These processes are fast, allowing us to drive to work without thinking about how to turn the steering wheel each time we get into a car.

Automaticity is hard-wired into us as an evolutionary requirement to ease cognitive resources. "The brain is considered a costly organ to run," said senior author Timothy Ryan, a professor of biochemistry at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

Suppose there's a hard limit on the energy supply to the brain. In that case, we suspect that the brain may handle challenging tasks by diverting energy away from other functions and prioritizing the focus of our attention.

A recent study’s findings suggest that the brain allocates less energy to the neurons that respond to information outside the focus of our attention as our task becomes more complex. This explains why we experience inattentional blindness and deafness even to critical information that we want in our awareness.2

Researchers have connected people's experience of brain overload to what's happening inside their neurons. High energy demands for one purpose are balanced by reduced energy use related to any other purpose. When we try to process too much information, we may feel the strain of overload because of the hard limit on our brain capacity.3

When our brain is at capacity, we operate in automatic thoughts and behaviors to bypass peaking capacity. We might not even notice a vital email coming in because our child spoke to us. Or we may miss the oven timer going off because of an unexpected call. Or we lose our train of thought as a pretty girl or a good looking guy momentarily dominates our field of vision.

The research can explain those often-frustrating experiences of inattentional blindness or deafness. Distraction is “the process of interrupting attention” and “a stimulus or task that draws attention away from the task of primary interest.” In other words, distractions draw us away from what we want to do, whether it’s to accomplish a task at home or work, enjoy time with a loved one, or do something for ourselves.4 Look at the graphic below.

Don’t get me wrong; this autopilot thinking can be beneficial as it frees up our attentional resources, so we don't become overwhelmed by small tasks. First, it's efficient. By slipping into this automated mode for routine tasks, we can function quickly and efficiently without paying attention to every tiny detail. Imagine how laborious and dull our day would be if we had to remember and think about how to drive a car, brush our teeth or take the trash out.

The second benefit of automaticity is that it allows us to feel comfortable and familiar with different environments. Through our experiences, we learn what is usual and expected in similar situations, like buying groceries at a supermarket. Every supermarket is different, yet similar.

The key is understanding, recognizing, and becoming intentional with our evolutionary wiring and usage of automaticity for our most favorable ends.

Think of automaticity in two ways. First, unconscious automaticity is a process that does not require any willful initiation and operates independently of conscious control. These processes can be instigated by stimuli that are not yet aware of or stimuli that are no longer 5. Envision reaching for your pinging iPhone.

Second, conscious automaticity is the behaviors we are aware of and do daily. These behaviors are often acquired skills, actions that become automatic only after significant repetition, like driving a car.

Outside most academic circles, there is one more way to think of automaticity, which is mastery, but I will save that for another time.

Risks abound even with the evolutionary perks of energy saving enjoyed by automatic thinking. Automatic thinking takes a toll in many areas of our lives, from making costly errors at work to the more mundane, day-to-day dangers, such as following a crowd across a busy street into oncoming traffic. Attention grabbing distractions are every where it seems but none more consuming than our little handheld portal to the world affectionately called a smartphone.

In August 2018, research from the UK’s telecoms regulator, Ofcom, reported that people check their smartphones on average every 12 minutes during their waking hours, with 71% saying they never turn their phone off and 40% saying they check them within five minutes of waking. 6 Consider our web-based world the graph below depicting respondents’ reactions to being unable to connect to the internet. Many of us feel adrift without an internet connection and its firehose of distracting information.

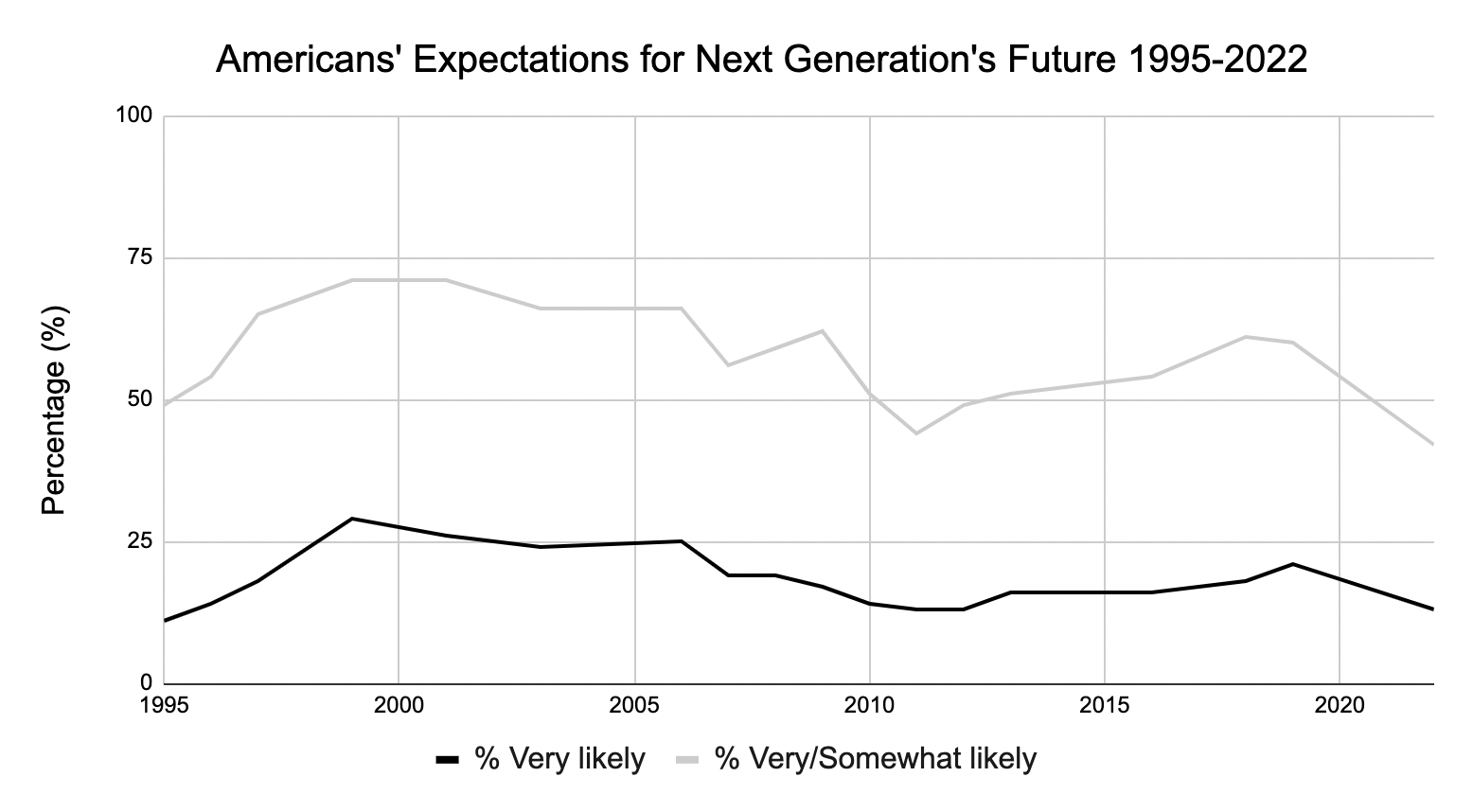

In our zombie state of automatic thinking and crowd following, we not fully engaged in crafting our lives or futures. It should be no surprise to see life satisfaction sinking and future expectations for our next generation falling.

To offset our world of distractions, I recommend a simple diet of mindfulness and using checklists to keep us on course. Mindfulness brings our awareness to the present moment allows us to interrupt automatic behaviors that we have internalized. Professionals in fields like healthcare and airline pilots utilize a verbal checklist system to combat automaticity of being and dangerous distractions. By repeating vital information to witnesses or associates, we gain a necessary crosscheck to our actions. Both methods can force us to be more present and less distracted.

I use this quote to bring my life into a better perspective. “We must fall in love with our passions, not our distractions.” Sorting out our passions from distractions is essential to pushing through challenges and finding what truly juices our everyday.

Until next time. Travel safe.